Up Close and Personal…

An excerpt from – Hunting Life, Moments of Truth. By Peter P Ryan

Up Close and Personal

FOR FOUR DAYS WE CIRCLED water looking for the right spoor. Buffalo hunting is a bit like sex and religion, in that ‘right’ means a lot of things to a lot of people . In that time we saw hundreds of tracks . If you’ve ever watched buffalo come in to drink, you’ll know about dust clouds rolling ever closer, heavy thorn snapping as they surge to slake their thirst, the final basso profondo grunts as they wade into cool waters .

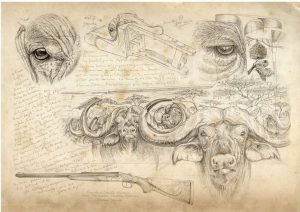

Among them are the herd bulls, heavy horns running to long tips, many still a touch soft in the boss . Sometimes, following in the vanguard as old soldiers are wont to do, there may be a dagga boy or two . Everyone knows that dagga is mud, the kind that plasters huts and cranky old buffalo, too. It is these ancients dogging the tail of the herd, hoping for one last swing in the big game, that interest us . Young bulls joust and jostle among themselves just as young men do, but old bulls give you the flat, hard stare they give to lions . I hate you. They mean it . They have proven it many times . Today there are no old warriors, so we watch the herd drink, knowing that just out there wading to the belly are bulls in the mid-forties and higher, bulls that taken anywhere else would be the achievement of a lifetime . We watch them turn and grunt and drift back into the vast emptiness of the reserve. That was the first choice.

Maybe that’s jumping too far ahead . Mpahleni Madonsela, better known as Patches, is something of a legend. He’s the one out front on buffalo, on the crazy tracking hunts they do for lion here in the Kalahari . No baits; just spoor the big cat up and sort it out in the ocean of blackthorn and grass . There are good numbers of lion spread out somewhere between here and the southern boundary 70 kilometres away. Patches will happily set off unarmed and follow a trail . Those giant prints, so shocking in size on the fine red dust of the tracks, turn to a whisper in the grassland, until the hands crossed behind his back move to a silent point . Just ahead . Just another day at the office. It’s Patches who is out front of me now as we thread through the bush, and I’m glad of it .

Walking next to me is Hans ‘Scruff’ Vermaak. As hunting pedigrees go, his is hard to beat: a family centuries in Africa, fourth-generation PH, roots stretching back to a hundred years of guiding . He’s a good man, in it for the long haul .

Scruff and I swap fireside stories each night over sundowners. I talk about the places I know best, of red stags and tahr near my home in New Zealand, but steer clear of any African swagger . I know that the record of my .375 H&H — hanging nearby on some gnarly shooting sticks — just doesn’t shift the freight here. This rifle has taken a handful of Cape buffalo and Asian water buffalo in Australia’s Northern Territory, but that’s paltry stuff to a pro in his third decade on dangerous game .

Neither of us has any interest in a herd bull, despite the way all those inches look on a score sheet. I flick through our photos from previous days. A youngster with huge mass and spread, but his boss smooth and all his breeding still to come . Another with pot hooks that go back forever, the kind of thing that can put your name high in the books, but still soft . He’s the sort that the average sport would lose a finger to take, but he won’t have the bad temper and character that comes with age . All of them given the look-over at 30 metres or so . Catch and release . In my youth I hunted herd bulls like them myself . I was proud of it then, and would not trade those memories for anything . But today I would not do it .

Why? When you get away from first-time clients and talk to the old hands of Africa, the tables turn . Most will tell you that a dagga boy is the one that gets them excited, regardless of the tape measure . They love the charisma and that long, hateful stare .

The European hunters of old were custodians . Their massive red stags came from centuries of treasuring the worn-out veterans as trophies, and ruthlessly culling anything unfit to breed. They produced the most stunning wild stags the world has ever seen . But they didn’t get that gene pool by shooting the best in their prime . When the antlers of a great stag are at their peak he’s a Zukunfthirsch — a ‘stag of the future’ . For them it was a crime to kill an animal at the height of his life, but a virtue to take him in old age, his breeding done and nothing to come but winter and a bad end. It might occur to you that this is the opposite of what much of our hunting has become. It might even occur to you that maybe, just maybe, we have it wrong and they had it right . If it does, then that question might lead to a choice, a moment of truth.

It’s hot now . The bush doves began their insistent throbbing before sunrise . Now, four hours of steady walking into the trail, they are drowsy in the shadows . The two old bulls moved away from water last night at a steady pace, covering ground . It surprises nobody that the bush is growing dense, the spoor winding through thickets of thorn . It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve done this, the clichés will run through your thoughts . M’bogo . Inyati . Hemingway, Ruark and Capstick . Black Death . The .375 that felt so good on the bench now feels — as H .G . Wells would have it — like bows and arrows against the lightning .

Suddenly they’re right there, twenty paces away . If you shoot, he’s so close there will be almost no time for a follow-up . But if he turns just a little and sees us with those bloodshot eyes, the distance is so short that he may just drop into a flat charge anyway.

The seconds before opening the game with a true dagga boy are a precise hunting moment . He can run faster than you, much faster . Out here, on the vast, empty Kalahari, there’s nowhere to run, nowhere to climb . In a moment or two you’ll bring the rifle to your shoulder and nobody knows what will happen .

That was the second choice

After a dozen safaris I know what I don’t know, and that the words of the wise heads around the fire are worth more than anything I’ll ever write. Some of them were damn funny, too . The tough Zambian with the .470 double who said he needed it to clean up because so many of his clients shoot doubles now, or try to . The PH in Zimbabwe who took me out in front of a huge herd of buffalo near the Hwange boundary, right on dark. There were lions behind them. The lead buff slowly grazed right past, until they caught our wind at just a few yards and stampeded back through us . We heard the lions make their move, but saw nothing in the darkness . If inyati truly is Black Death we would never have walked out . We used up some luck there .

Another truth, a harsher one . It takes a certain nerve and skill at arms to make a cool shot on buff, but client talk about stopping charges is mostly vanity. Clients need a rifle that they can make a great first shot with, not a close-range stopper, which is a different tool altogether. After two decades of

Eye contact

African hunting I’ve known several professionals gored or otherwise stomped by game, but no clients . None .

And the reason for that is simple . A busted client is bad for business and puts a licence at risk. With a wounded buff you might be asked to walk behind as backup, but the truth is that no PH is going to ask a client to sort out a problem .

If you can shoot a heavy rifle with open sights really well, then take it. Most men can’t, but pride won’t let them say so. They would be better off with something they can shoot with precision . I can’t imagine what it would feel like to pay someone to sort out a mess I created, then put it on the wall at home, but it happens . Usually it is because vanity demanded a cannon with express sights that proved too much for middle-aged eyes . So, another choice to make .

The seconds stretch out . Any moment now he’ll turn and see us and it will all go to hell . Your heart is racing while the basic checks run . Watch out for that hole. Safety is definitely off. Scope is down to true one power. There’s a tiny tree over there that might buy a second or two if things go wrong . That’s where Patches is, fading back . The wind is shifting and the bull has taken a step, getting suspicious . You take a long breath, just long enough to taste the moment for what it is . You’ve come a long, long way for this, but so has he. All of a sudden you’re looking at a black bull through the Swarovski, and the roar of the .375 shatters the noonday silence . You don’t even hear it, before the rifle comes out of recoil you’re throwing the bolt, all those years’ experience take over and make your hands do what they need to do . The bull stumbles, but is up again in a flash. Your second shot catches him on the run and he’s down within 10 metres, a short run even for a heart shot. His brother with the flaked-off, bare-bone boss hasn’t read the script. He doesn’t run, but circles and stands at 40 metres, nose up and eyes boring straight through your soul. “I hate you. Friend, if you do come, it will be a fistfight. Here’s how it will go. I’ll try to break you down with the .375, but chest-on it’s sketchy. At 20 metres the Krieghoff double next to me will speak, then again in the final second. After that, everyone is on his own. So we wait . He circles again, probing . Hunting writers insist that these seconds be called ‘an eternity’ . They are not . They are a lucky gift from the hunting gods, because they allow just enough time for a truly existential moment. ‘This is me, watching a son-of-a-bitch buffalo decide whether he wants to kill me, right now . And that’s okay .’ You pay for these moments, so it’s best to enjoy them. Eventually the bull throws his head back with a grunt and see-saws his way off into the thorn. Somewhere in the long grass a few feet away is your bull, condition unknown.

In front of you lies a big, black beast, his shoulders shocking in size, his boss like a heavy timber beam, covered in green bark from the trees he crashed through yesterday. He had a big life, lion and fighting scars all over . Proper rock-hard boss, so many inches gone from heavy worn-down tips, teeth vanished to the gum-line . His time would have been measured in months .

It’s a win, but an old warrior has fallen at last . The solace is that his sons are roaming around out there, fighting their way through herd life to the cows, doing what Africa does. It’s only afterward, over a fire, that you begin to realise the gifts that hunting this way can bring . Horns to remind you of days wandering the wilderness? Certainly . Five hundred meals for proteinstarved people, and the fee paying for anti-poaching patrols? All true, as far as it goes .

But there is another thing, one you never see in the brochures, never see in the social-media posts of sports posing with high-horned youngsters . Your buffalo has given you many moments of truth. You had to pass all of them to get to this one .

We love the Big Five for what they are, but in turn the hunting of them teaches us who we are — if we choose to listen . And that’s another choice, another moment of truth.

THE TROUBLE IS, YOU THINK YOU HAVE TIME

But the lives we live today come with a lot of baggage . Renewing insurance . Recovering lost passwords . Cleaning the gutters, answering emails . Just touching up a fence or hanging a gate can soak up the hours . None of this is hard work, to be sure, but when you pause and watch the

ducks circle and gang up and call to each other it’s hard to bear.They sense the change of season, the restlessness in the air, in the trees, in themselves .

Yes, there is work to be done, a hundred small cares and duties.Yet I see them winging across the broken autumn sky, the wanderers of wild places, and wish that I could follow.

It’s time to pull the decoys back out of the shed again…, the old ones knocked around by another season, the new ones looking almost too bright and vivid by comparison. My old swan confidence decoys are nowhere to be seen. A pity, as I liked them; they probably gave me more confidence than the ducks. There’s a story behind it all, for sure, but today it doesn’t matter, we’re off to a stubble field to set up against a fence line, right by the river…

Peter P Ryan